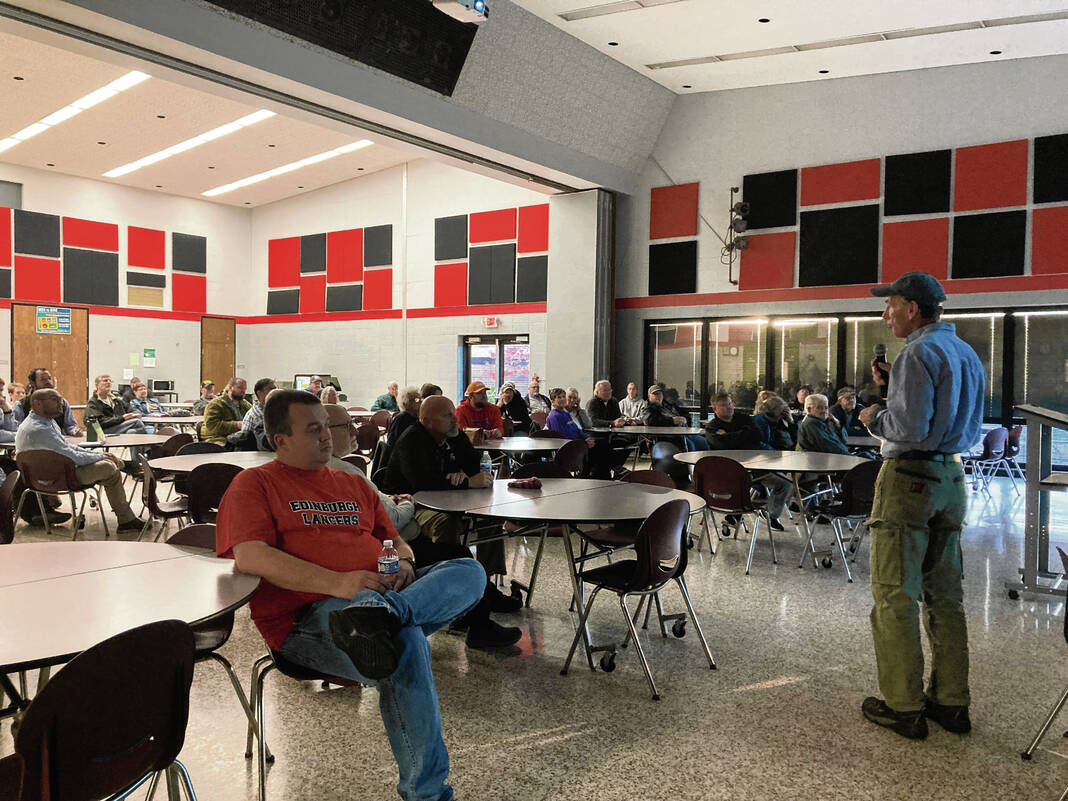

Edinburgh officials hosted a town hall Thursday evening to relay information to the public regarding the recently failed Thompson Mill Dam and to seek ideas on how they can commemorate the landmark.

Town Manager Kevin McGinnis said that the town has learned a lot regarding low-head dams in the last few weeks and the leadership in the town understands the importance of the decision when it comes to either removing the current dam in the river, repairing and replacing the dam, as well as the possibility of leaving the dam in its current condition.

“We’d like to keep it forever, but given its current condition, figuring out what to do with the dam is a very complicated matter,” McGinnis said. “This dam was built by Thompson Mill to use the water to generate a turbine that would mill wheat and turn it into flour. It was not built for anything other than to direct water through for power generation.”

Both McGinnis and Jerry Sweeten, a senior ecologist at Ecosystems Connections Institute, both presented at the meeting. Sweeten had previously spoken to the town council about the dam last month.

The meeting primarily focused on the dangers the dam poses and the high cost to repair the low head dam if that was the town’s objective.

“The leadership of the town understands the emotional ties to the dam,” McGinnis said. “The cost to repair this dam is in the millions. I don’t want to get rid of the memory of the Edinburgh dam.”

Repairs could cost millions

McGinnis projected the cost to repair the dam to be around $3 to 5 million, which the town of Edinburgh does not have lying around, he said. The Indiana Department of Natural Resources, or DNR, also likely would not issue a permit to allow the town to repair it.

According to a report by DNR on Oct. 23, and shared during the presentation by McGinnis, the Thompson Mill Dam’s foundation is compromised and a rebuild would require the town to completely remove the dam.

“Because of the damaged and compromised foundation, if there is a future initiative to rebuild a dam, a complete technical analysis, redesign and rebuilding of the foundation and dam will be needed,” the report reads. “This also would necessitate the removal of whatever remains of this dam. Many groups focus on seeking rebuilding grants over the years, even though grants for this type of work don’t seem to exist. When it comes to these old low head dams, the only grants we have seen were created with the focus of funding their removal.”

McGinnis also shared an email conversation between he and Jon Eggen, the DNR’s Dam Safety Program manager. He asked Eggen if he was aware of any funding that the town could use to repair the failing dam.

Eggen said he wasn’t aware of any, which was likely because low-head dams are known as “severe liabilities.”

“Due to the many recent deaths at low-head dams across the nation, agencies may be reluctant to insert themselves into situations where they could become liable due to funding the construction,” the email read. “The other big issue is that there is a nationwide push to remove these structures to restore the ecosystem. Also, because of these issues there is no guarantee a new permit could be issued without significant mitigation to prevent drownings and maintain the resource.”

In 2014, the dam claimed the lives of two Franklin teenagers. Even the strongest swimmers wearing flotation devices have drowned at low head dams because of the intense water current beneath their walls, according to DNR.

Preservation issues

Other issues lie with the preservation of the dam as well. Even though the dam was completed in 1884 and deeded to the town in 1954, the structure is not registered as a historical site by the state of Indiana, nor is it registered as a landmark by the National Historic Landmark Society, McGinnis said.

The dam was last inspected in 2022. Low-head dams are to be inspected every five years. Even before the last inspection, the dam was noted to have been leaking and falling apart, he said during the presentation.

“The dam is not keepable,” McGinnis said. “We do have a grant right now that would totally take it out and stack the remnants of the dam in a location designated by the town. The reality is that it is a bigger issue than what most of us are thinking about. Maybe the time has come, but that’s just my two cents.”

If Edinburgh commits to removing the Thompson Mill Dam, the town will be given a $700,000 grant which would fully fund the removal of the dam with no liability to the town. If the dam is removed, McGinnis also said the $1 million liability coverage the town currently has for the dam could be put toward other expenses.

The town has a time crunch to make a decision, because if the dam were to fall apart more before it is removed, the town would no longer be eligible for the grant. The option to leave the dam in its current condition comes with some caveats as well, officials said.

“If the dam continues to degrade and the river is flowing naturally, then it will get much tougher for our program to support the removal of a barrier that is no longer affecting fish passage,” said Kevin Haupt of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “If there is a commitment from the town as we continue to move forward, we are not going pull funding if something happens to the dam.”

Impeding the waterway

The town owns the dam, but the Big Blue River is a state waterway. Because of this, Edinburgh could be mandated to remove the dam by the state if it further impedes the waterway after it collapses, McGinnis said.

“If our dam falls apart and interrupts the waterways that the state owns, we could be fined or in trouble with the state or have to get the remnants out of the state’s waterway,” McGinnis said. “Then the town has to come up with $700,000 to get the stuff out of the waterway.”

The grant is based on the fact that low-head dams, including the Thompson Mill Dam, stop fish from migrating upstream. These grants are in place to restore the ecosystem and allow the fish to swim up and downstream as they are naturally driven to do.

“In Indiana we have over 200 species of fish,” Sweeten said. “Most of those fish need to migrate upstream and downstream as part of their life. When they hit a dam, it breaks that cycle.”

Sweeten has been a part of a team that has removed several dams in Indiana and has researched the ecosystems presented before and after the removal of a low-head dam. His team has been hired by the town as a consultant.

Although it takes about a year for the waterway to fully heal after it is removed, Sweeten has witnessed dramatic improvements to the ecosystem once removal has taken place. It will even improve the location’s fishery, he said.

The grant would also allow for the relocation of the dam’s building materials. The limestone blocks could be kept as mementos of the dam, Sweeten said.

McGinnis proposed that the town could approach the schools and have students come up with a design for a monument to be made out of the limestone blocks. The town could build the memorial near Thompson Mill, he said.

He also encouraged community members to submit their ideas on how they could commemorate the history of the dam with the blocks.

Historical methods

James Heimlich, historian and archaeologist for Orbis Environmental Consulting in South Bend, said that there may be more to the dam than meets the eye. An older portion of the dam with wood timbers is now exposed above the water, he said.

“You will learn more if we can control the removal of the dam. You will gain knowledge and history through this process,” Heimlich said. “Inevitably, it will be removed either by nature or by choice. We are actually preserving history through a controlled removal.”

Those timbers could potentially be preserved as well, he said. Heimlich also attested that he has never seen this amount of quarry limestone blocks used in a dam, said it is a very rare find.

“If it were still in good shape and it wasn’t breached, it would probably be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places,” he said.

Low-head dams were a major historical phenomenon that helped build the nation. In the 1800s, most everything was powered by water and dams like Thompson Mill were instrumental to the country’s growth. However, with the invention of electricity and other methods, their purpose has waned over the last century, Heimlich said.

If the limestone blocks were to be assembled into a monument for the town, these blocks would be around for hundreds of years if not longer, he said.

Residents reminisce

With over 60 Edinburgh residents in attendance, several voiced their concerns over the dam, reminisced on its importance and asked questions to the presenters.

Lawrence McIntosh said it felt like a “prized possession” was being taken away. He also said it felt like the decision was already made to remove it.

“Have you ever been down there on a nice, sunny day and closed your eyes to hear the water rushing?” McIntosh said. “Now we hear that it is going to be gone. … How do we preserve that feeling that we used to have? How do we go down there when the dam is gone, when it is removed? We will have nothing to look at when we come home. I’m talking about saving the dam — I’m talking about creating a memory for our kids.”

When asked after the meeting if the presentation had changed his viewpoint in regard to saving the dam, McGinnis responded, “Absolutely not — I feel the same way about the dam as when I came in.”

One community member asked if a bid was conducted to conclude what the precise cost of the dam’s repair would be. Edinburgh Planning Director Wade Watson said that they investigated the costs associated with repairing the dam in 2013.

“It was going to cost a quarter of a million dollars just to de-water it and to get an estimate on if we could rebuild it,” Watson said. “We would have to pay $275,000 to get an estimate on if we could rebuild it.”

Another resident asked if townspeople would be required to buy flood insurance if the dam is removed, but McGinnis said that this would not be the case because the dam was not designed for flood prevention and would not affect flood zones.

Someone else asked if there would be a portion of Thompson Mill Dam left in Big Blue River after its removal. Sweeten said there is some flexibility in terms of how much of the dam would be left on each side — partly from a community standpoint and partly based on what ecologists would say is the safest amount to remove. A third factor would be whatever an archaeologist would want to preserve so people could see what it was like.

The Edinburgh Town Council could make a decision on the dam during their next meeting later this month.